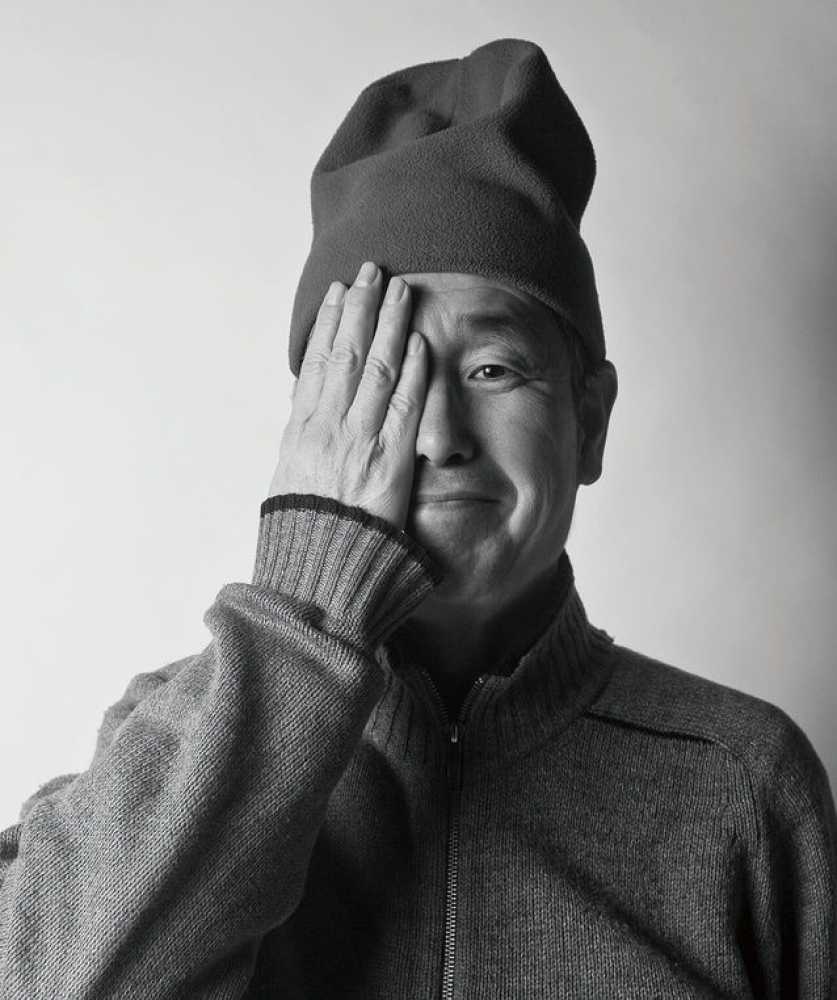

Founder

Kengo Kuma & Associates

Kengo Kuma, a world-renowned architect, has made an indelible impact in the field of architecture by redefining the relationship between nature, technology, and humanity. Since the founding of Kengo Kuma & Associates in 1990, Kuma has brought his vision of blending architecture and its environment seamlessly to life. Kuma’s design philosophy, which prioritises natural materials and human-scaled spaces, can be seen in some of the world’s most iconic structures.

He is an Honorary Professor at the University of Tokyo, and taught at prestigious institutions like Keio University. Kuma continues to share his knowledge with future generations of architects. His philosophy integrates traditional Japanese aesthetics with cutting-edge technology, creating architecture that is both grounded and forward-thinking. Kuma’s influential body of work includes notable publications such as “Onomatopoeia Architecture Grounding”, “Natural Architecture”, and “Small Architecture”.

The DFA Lifetime Achievement Award 2024 celebrates Kengo Kuma's pioneering vision and his profound contributions to the world of spatial design. His talent for blending natural materials with modern design principles offers a new perspective on how we engage with our surroundings, fostering a deeper connection between people and the environment.

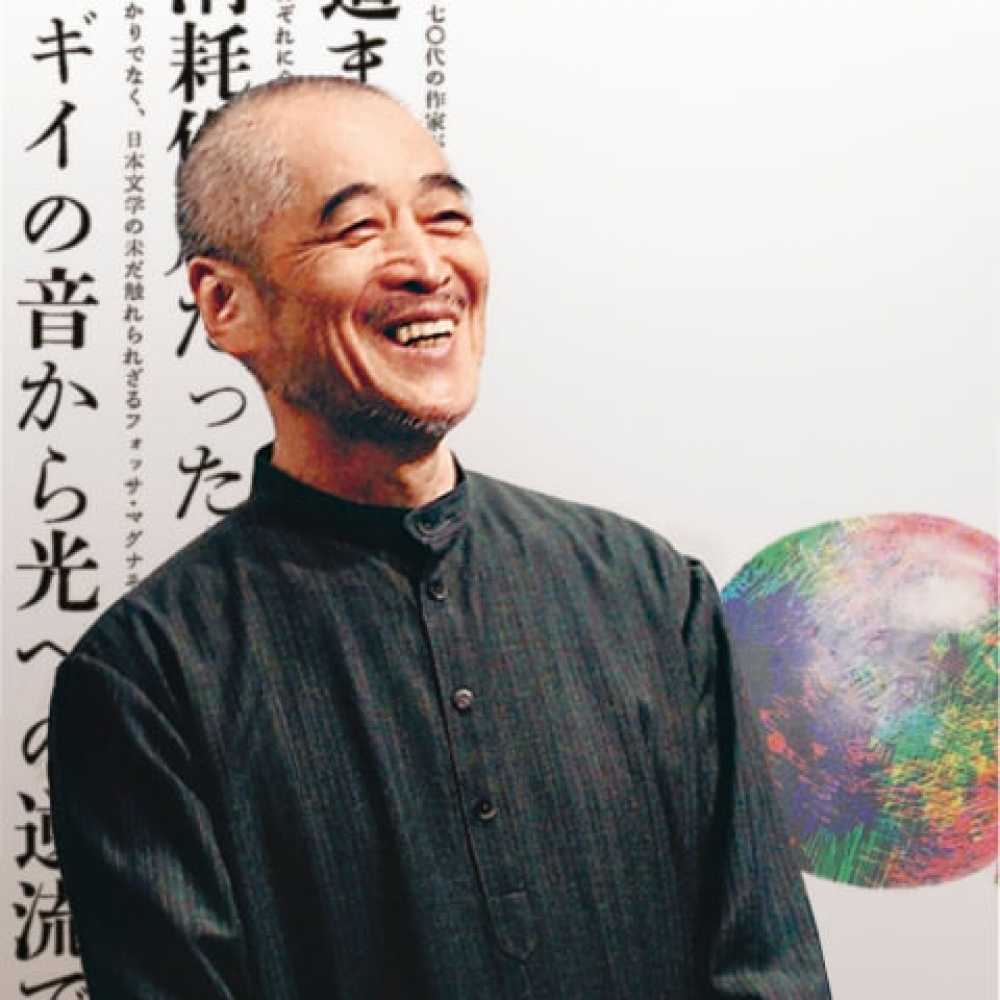

Kenya HARA, a distinguished Japanese graphic designer, renowned as the founder and director of Hara Design Institute, has undoubtedly made an indelible impact on the realm of communication design.

After graduating from Musashino Art University in 1983, Kenya HARA embarked on a path that would redefine the role of design in our everyday lives.Mr. HARA's influential contribution to MUJI, as a member of its Advisory Board since 2002, has been of paramount importance. His focus on the concept of 'Emptiness,' a cornerstone of MUJI's minimalist design philosophy rooted in Zen principles, has significantly influenced the brand's aesthetic.

Throughout his illustrious career, Kenya HARA has embraced a wide spectrum of design projects, showcasing his versatility and creativity. Notable among them are his remarkable works on the Opening and Closing Ceremonies of the Nagano Winter Olympic Games and Expo 2005.

Besides, Kenya HARA has also made significant literary contributions to the field. His books, including 'Designing Design' and 'White' have been translated into numerous languages and achieved widespread global recognition, further solidifying HARA's influence and impact.

The DFA Lifetime Achievement Award 2023 celebrates Kenya HARA’s enduring impact on design philosophy, his talent for making the ordinary extraordinary, inspiring individuals to find wisdom in simplicity, fostering shared human experience, promoting understanding and sensory peace.

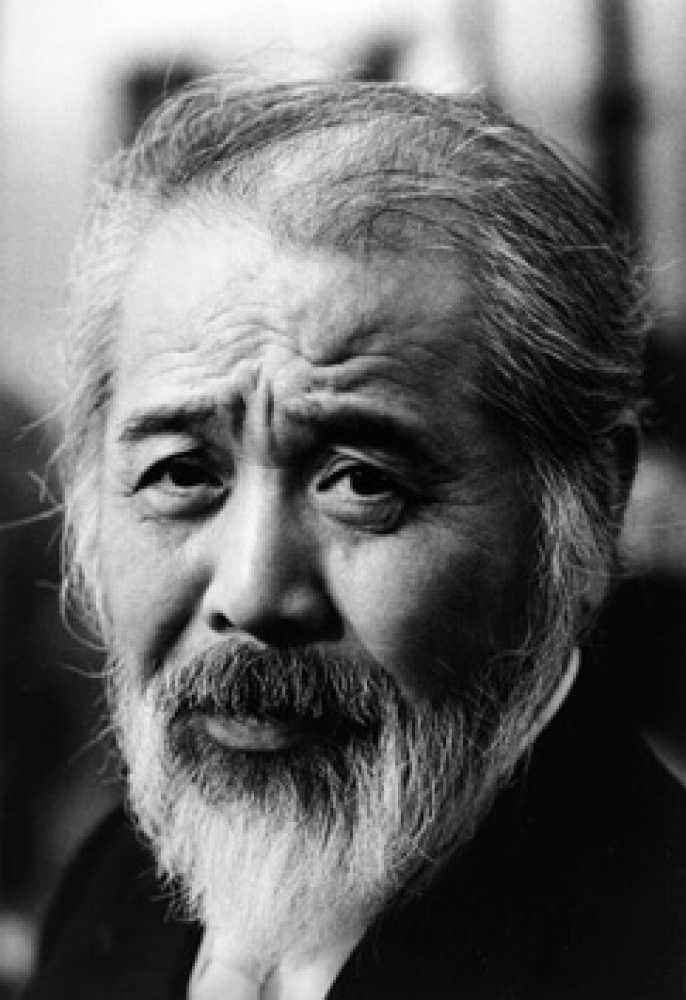

Founder

Katsumi ASABA Design Studio

Born in 1940, Katsumi ASABA is a Japanese designer, art director and master calligrapher based in Tokyo. He has a particular interest in the rich cultural heritage of writing in Asia and in exploring the relationships between written and visual expression.

After graduating from Kuwasawa Design School and working for Light Publicity Inc., he founded Katsumi Asaba Design Studio in 1975. Since then he has taken an active role at the forefront of Japanese design industry. As an art director, he has many creations which have made a lasting mark in the history of Japanese advertising design. Representative works include landmark ads for Seibu department store, Suntory, and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, and Logo design for HOMME PLISSÉ ISSEY MIYAKE. He has received numerous awards including Tokyo Type Directors Club Award, Yusaku Kamekura Award, Japan Academy Prize for Outstanding Achievement in Art Direction, Medal with Purple Ribbon, Tokyo Art Directors Club Grand Prix, and Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette.

He is the chairman of the Tokyo Type Directors Club, Committee Member of the Tokyo Art Directors Club and JAGDA (Japan Graphic Designers Association), Japan’s representative in the Alliance Graphique Internationale, 10th successive director of Kuwasawa Design School, and visiting professor at Tokyo Zokei University and Kyoto Seika University. He also holds the title of sixth degree master in table tennis.

Executive Chair

IDEOTim BROWN is the Executive Chair of IDEO, an international innovation and design firm. He holds honorary doctorates from The Royal College of Art (London), Keio University (Tokyo), Claremont McKenna Graduate University (Los Angeles), and ArtCenter College of Design (Los Angeles). With a background in industrial design, he has won numerous design awards and had his works showcased at various galleries and museums internationally.

“Design thinking”, Brown’s design philosophy, is a human-centered approach to design innovation that integrates the needs of people, the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success. Brown has accomplished remarkable achievements throughout his career. Being design thinkers, he is the author of the book “Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation” which was published in 2009. He launched OPENIDEO, a collaborative platform for design success and IDEO U, an online school for creative success in 2010 and 2015 respectively. Brown is also involved in a variety of roles, including advising senior executives and boards of global Fortune 100 companies, writing for the Harvard Business Review, The Economist, and other prominent publications. Currently, he is one of LinkedIn’s original top 150 Influencers and continues to impart his insights on the value of design thinking to business leaders and designers around the world.

photographer credit : ©Paolo Roversi

Possessing an inquisitive mind, a free spirit, and acute business acumen, Rei Kawakubo founded the label Comme des Garçons in 1969 amid social upheavals and scientific discoveries that have shaped the world we live in today. And since then she has been creating avant-garde designs, which express her own values, not just about making clothes. Trained in fine arts and literature at the prestigious Keio University, Kawakubo turns designing, making, and marketing clothing into a choreography of contrasting shapes, unconventional materials, and evocative cultural references. The resulting apparel becomes a seductive enigma that beckons one’s gaze onto the persona presented by the connections as well as the disjuncture between couture and the human body. Her works are designed to be desired, deciphered, and deconstructed.

Designer

Photo by Kazumi Kurigami

For 45 years, YAMAMOTO has been working in the fashion industry. Renowned for his avant-garde style, his unique designs have graced international runways since his debut in Tokyo in 1977. He presented his first collection in Paris in 1981. In 2002, he was appointed as the creative director for Y-3. YAMAMOTO’s dedication to the fashion industry has been recognised the world over, and awarded lots of honours including the Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters, the highest honour in arts and culture in France.

Graphic Designer

Director, Paju Typography Institute in Korea (PaTI)

Photographer: Jung Jungho

Ahn Sang-soo is one of the most active Korean creatives in the global community. In 1985 in Seoul, South Korea, he founded the Ahn Graphics, leading graphic design consultancy with strong roots in typography and editorial design. Ahn had taught Hangul typography at Hongik University for the past 20 years, he believes typography is full of latent possibilities that allow us to free the typeface from stereotypes and breathe life into with our imagination.

For a young Asian democracy at a historical crossroads, Ahn created his first self-titled typeface configuration “Ahn Sang-soo” that won him nationwide fame. The bold circles and shorter strokes convey an unmistakable energy that portends of the cultural, social, and economic renaissance that have deeply reshaped Korea amid globalisation.

In 2010, Ahn founded the Paju Typography Institute (PaTI) in Paju Book City, offering practical training to students from diverse backgrounds wishing to work on typography at bachelor’s and master’s levels. In 2012, Ahn was appointed by the Seoul Metropolitan Government as the Chairman of the Board of Seoul Design Foundation and presided lots of game-changing projects, including the Dongdaemun Design Plaza. Over the years, he also served as the ICOGRADA Vice President, and took part in numerous typography exhibitions and events, the most notable of which is the Seoul International Typography Biennale. He also published, as both art director and editor, an underground art and culture magazine, bogoseo/bogoseo (report/report), after serving as art directors for various art magazines, such as Ggumin, Ma-dang, and Meot.

Former Chief Designer Porsche A.G.

Founder and Design Director Brainchild Design Group and Brainchild Design Consultants, Ltd.

Director, Research Institute of Asian Design

Kobe Design UniversityBorn in 1932 in Tokyo, Japan, Kohei Sugiura is a master of graphic design, typography and design research. After graduating from Tokyo University of the Arts with a degree in architecture, Sugiura entered the graphic design world in the 1950s. From 1964 to 1967, he was Guest Professor at the Design College of Ulm in (formerly) West Germany and Professor of Visual Information and Design at Kobe Design University from 1989 to 2002s, Sugiura is currently Director at the Research Institute of Asian Design, Kobe Design University.

Sugiura’s work crosses a wide spectrum within three fields — book and magazine design; research on Asian forms; and intricate diagrams. Among his many projects are book designs of Den Shingon-in-Ryokai Mandala: The Mandalas of the Two Worlds at the Kyoo Gokokuji in Kyoto (1977), and Zen Uchuushi (Summa Cosmographia) (1979); cover designs for Ginka (Silver Flower) Magazine (1970-2010); and unique diagram design of Time-distance Map (1969) and Distorted Globe on the Axis of Time (1971). He was also the planner and designer of several exhibitions including Beijing Opera in Japan (1979), Asian Cosmology (1982) and Floral Cosmology of Asia (1992), and has been commissioned to design Bhutanese postage stamps (1983-1985).

He has deep passion for the making of books and takes on many roles when designing them — as researcher, graphic designer and editor. His publications have been translated and published in various languages. Major work ranges from Asian and Japanese Forms and Designs, 1994 (Taiwanese edition 1998); Forms Come Alive: Spirits of Asian Design, 1997 (Chinese edition 1999, Taiwanese edition 2000, Korean edition 2001, English edition to be published in 2015); Books, Text, and Design in Asia, 2005 (Chinese & Korean editions 2005, Taiwanese edition 2006, English edition 2014); Wind and Lightening: a Half-Century of Magazine Design by Kohei Sugiura, 2004 (Korean edition 2005, Chinese edition 2006); to Multi-subjective Asia, Sounds, Light and Phantasm of Asia, and Spiritual Power of Character in the series of Kohei Sugiura’s Words and Thoughts on Design, among many others.

Recent exhibitions include “Vibrant Books – Methods and Philosophy of Kohei Sugiura’s Design” at Musashino Art University Museum & Library (2011) and “Luminous Mandala: Book Designs of Kohei Sugiura” at Ginza Graphic Gallery (2011).

Born in 1937 in the United Kingdom.

Specialised in Business applications for design, how design creates economic value, history of design and its role in economic and social change.

Charting a Bigger Picture of Design

Considering the reams of scholarly book titles, papers, and awards in his name, one would expect Professor John Heskett’ s CV to read like a design academic’ s dream career. And it does. But scratch the surface and it comes as a surprise to learn that his route into design was not obvious. Having studied Economics, Politics and History at the prestigious London School of Economics, he took a job as a town planner at Norfolk County Council. So this was his link into design academia? Not quite.

In 1964 he found himself in Australia where he found employment teaching secondary school history. It was here that he got caught up in, what was then and some would argue still is, a hugely contentious issue for Australians, that of their cultural identity. With a view of global culture, Heskett is talented in looking outwards to the big picture in design. His peers, as well as judges of this Award, have commended his ability to connect Hong Kong to the international, and this is important to designers in Hong Kong where cultural identity and positioning continues to be debated at length in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

With a Systematic of design knowledge to explore the design policy

It was when he joined Coventry College of Art (now University of Coventry) in 1967 that Heskett, with the avid support of the Head of Design, proposed some radical new ideas for their design programme. They were convinced that design students should not just be taught design history, but should have a much broader view of the context of design, one that questions its cultural relevance in the wider world, is more systematic in thinking, and embraces socio-economics and business. It is worth noting that the phenomenon of globalisation was not even a pinprick on the horizon at this point. This enabling him to “do work that genuinely asked questions and required me to dig in and learn and develop totally new courses that were not being taught elsewhere.”

Later, having moved to what was then Sheffield Polytechnic; he started exploring aspects of design policy. He was later able to put that research into practice when invited to Mexico in 2008 to give a series of lectures to universities and various layers of government, including members of the Congress. The response was incredible and ultimately led to Mexico establishing an academic-run national council for design.

Heskett is not a designer, but when he utters the words design policy and design management, eyes tend to glaze over as it is not obviously tangible. “We are talking about design as a meta-study or meta-theory, it emphasises the larger patterns of the structure of any form of practice,” he explains. “It is linked to practice very closely, it depends upon its capacity to understand, recognise, articulate and analyse what is happening in any particular field and provide operational structures for creativity to become effective.”

He is vehement in his arguments about the need for a structure of knowledge and illustrates this further by referring to the discipline of architecture. As he makes clear, for any form of design it is a matter of relevance –what does it mean for the people for whom it is intended. This, he believes, is central to the question of design as knowledge.

Design is a meta-study or meta-theory

Interestingly, Heskett makes no apologies for not possessing an artistic or creative background – Though among his bookshelves you’ll find the original hardback edition of his opus title, Industrial Design, published and still in print. How does he explain its remarkable longevity? “I think for the first time, someone wrote a book about design that treated the field as having its own theory and history, and that is based on the positioning of design in the context of work, that is the world of business, unlike an artist,” he says. “Designers were being educated on the basis of them being artists not designers. The book was an attempt to change that and it did seem to have considerable impact in the early years.” Indeed it was, and probably still is, a bible for those in design education.

“By mid-1990s, I had been at Illinois five years and began developing courses on design and economics; how design creates economic value,” he says. This was a new direction, focusing on how to send students out into the world of work with the capacity, and vocabulary, to discuss and argue the case for design.

This area of design theory and management has occupied a substantial chunk of Heskett’s academic development and it is something he continues to champion. When asked if anything concerns him about Hong Kong’s future, there is the issue of Mainland China, but Heskett has a somewhat different take on it. “I always say that China did not take over Hong Kong, Hong Kong took over southern China,” he says, reflecting on a staggering statistic quoted by Hong Kong Design Centre Chairman Victor Lo. “Before the handover there was a million people employed by Hong Kong in southern China; in 2010 that had risen to 15 million,” he says. “It raises the question of how you educate students to cope with that; it’ s a whole new area of thinking and new issues are arising but a lot of it is positive – taking the old Chinese adage that problems present opportunities.”

Founder

Steiner & Co.Clearly Culturally Intelligently

Cross-cultural Design Pioneer, Henry Steiner claims there is no such thing as a “typical Steiner design style”. His creativity remains deeply rooted in his European origins, an academic mentorship under the renowned Yale educator Paul Rand and admiration for design gurus such as Henry Wolf, Tanaka Ikko, Milton Glaser and Ivan Chermayeff. He also credits a sojourn at Paris’s Sorbonne and his early career at Asia Magazine in New York amongst his most formative influences. A lifetime passion for Japanese art and 50 years of living in Hong Kong have also helped him create acclaimed work for clients such as Acer, Asiaweek, Chase Manhattan Bank, Dow Jones, Far Eastern Economic Review, Hilton, HSBC, IBM, Jardine Fleming, Mandarin Oriental, San Miguel, Shangri-La, Ssangyong, Standard Chartered, Prudential and Unilever.

Henry Steiner will tell anyone who cares to listen that design is a cross-cultural solution at an urban crossroads and an effective left-brain/right-brain confluence. Most importantly of all, Steiner will tell listeners that design is about intelligence. “Some designers want to be artists, some artists designers. I never wanted to be anything but else but a graphic designer and think I was the first person in Hong Kong to claim to be so.”

Born in Vienna but raised in the US, Steiner moved to Asia in his 20s having developed a love of Japanese style woodblock prints and the films of auteurs like Akira Kurosawa from an early age. “My most important early influences were Paul Rand who taught me methodology and Alan Fletcher. A Yale friend and colleague and a very important designer, Alan showed me that good designers try to solve their clients’ problems.”

Design is an intellectual exercise

For Steiner, professionalism means meeting clients’ needs and deadlines. “When people ask me where I get my inspiration, and I say – literally and without irony – from the deadline. My creativity is like a car that won’t start until the ignition sparks! Steiner believes there are four key principles to design. The first is “The analysis of the idea. This was the first principle Paul Rand taught me! A classmate once said, ‘I have a feeling, a sense of nature.’ Paul retorted, ‘Yes, but you don’t have an idea!’” Steiner’s second principle is that form must follow function. “While this is a truism, many so-called creative talents don’t consider it nearly seriously enough. To me, design means satisfying function.” And the third principle? “Context and content. There’s no need for further elaboration. You either get it or you don’t,” he says.

Steiner has similarly strong views on style, claiming that designers who proudly claim to have a single style are among creativity’s worst enemies. “I can’t think of anything worse than people looking at one of my designs and instantly saying ‘Aha! A Steiner!’ I try to make every project I undertake different. At the end of the day, I design for the client, not for me! While style makes things prettier, design should add content that wasn’t there before.”

For Steiner, the client and the solution must always come first. “If I ever hear, a designer saying he or she will ask their client, ‘What style do you like?’, I’ll say you are the designer, you should be telling the client how to solve the problem!” The idea remains paramount in this process. “Designers must mentally envisage where the client wants to go and find a memorable way to express and communicate the idea that will take them there.”

The strength of a good brand is that it associates with something that is valid

Contrast is also crucial. Steiner recalls fondly that juxtaposition was amongst the most important lessons he learned at Yale. “Unexpected contrasts between what you know and what you don’t!. The ‘Yes, I’ve seen that before, but not like that!’ moment. Exploring what people expect and don’t expect can be very powerful. Take my studio’s Chinese zodiac. When we pictured a rat with a piece of Swiss cheese, Chinese people were amazed because it was the first time they had seen the traditional contrasted with the contemporary.”

Language is yet another fundamental aspect of design. “When you are solving a problem, clients often cannot tell if something looks good. As a heavily right-brain person I am useless with numbers. Clients tend to be very left-brain oriented and love facts and figures. So you have to give them an explanation they understand. My company’s design for the HSBC logo was based on the company flag, but we put ears on it and created more triangles to symbolize East and West. HSBC made the connection straight away.”

.

“Most left-brainers are as unskilled graphically as I am with numbers. Not in the sense that they can’t see, but in that they cannot perceive things like contextual relationships.” A commission from a Japanese company financial company provides a useful case in point. “Our concept consisted of a round Japanese coin with a small cut-out square in its centre. Graphically, we showed a circle and a diamond, both of which are very auspicious, especially for a financial concern.” Steiner cites his team’s use of a floorplan-stye logo which contains the Chinese character 壽 (longevity) for Hongkong Land as being another example of this thinking in action. “It is vital to speak to people in ways they understand”. Steiner concludes his train of thought with typical humility and honesty. “I believe people tend not to think about things with which they don’t have a problem. The best solutions are the ones that are indestructible and cannot be screwed up, regardless of who uses it and how. There really is no point in reinventing the wheel! The longer something stays the same, the better it becomes.”

A designer should not have a style. This is a serious threat to design

Established in Hong Kong in 1964, Steiner & Co. is one of the world’s leading branding design consultancies having undertaken work spanning everything from corporate identity programmes and packaging to book and magazine design and even coins and banknotes. Major clients include EF Education First, Hong Kong Jockey Club, HSBC, and Standard Chartered Bank. Steiner’s distinguished body of work has led to professional recognition such as Presidency of the Alliance Graphique Internationale; Fellowship of the American Institute of Graphic Arts, Chartered Society of Designers, and The Hong Kong Designers’ Association. He is also an Honourary Member of Design Austria; and a Member of The New York Art Directors’ Club.

Steiner has been named Hong Kong Designer of the Year, a World Master by Japan’s Idea magazine, and is included in Icograda’s Masters of the 20th Century. Next magazine hailed him as being one of the 100 most influential people in Hong Kong’s history. He was also awarded the Golden Decoration of Honor of the Republic of Austria (2006) for design achievement and received an Honorary Doctorate (2004) from Hong Kong Baptist University. He is also an Honourary Professor at School of Design, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Books Henry has written or co-authored include Cross-Cultural Design: Communicating in the Global Marketplace and Henry Steiner: Designer’s Life.

Founder & Chairman

GK Design GroupKenji Ekuan has held prominent design positions throughout his life. He was the Executive Chairman of the Organizing Committee for the International Council of Societies of Industrial Design at the 1973 Kyoto Congress; President of the Japan Industrial Designers’ Association; President of the International Council of Societies of Industrial Design; General Producer of the World Design Expo ’89 in Nagoya. He is the Chairman of Design for the World, the humanitarian organization, as well as holding important positions in the Japan Design Foundation and the Japan-Finland Design Association. He is the founder of GK Design.

His numerous awards include the prestigious biennial Osaka International Design Award; the Colin King Grand Prix; the Sir Misha Black Medal (UK); the Order of the Rising Sun (Japan); and, a Commander in the Order of the Lion of Finland. He is the recipient of the inaugural Design for Asia Awards’ Lifetime Achievement Award 2011.

Pioneering Humanist Design Master

Kenji Ekuan is the venerable and highly respected Japanese designer who has been instrumental in initiating global design trends and whose unique contribution to design has also covered speaking, writing and designing using a philosophical, erudite and intellectual approach, while also ensuring that design meets people’s everyday needs.

Ekuan-san is the inaugural recipient of the Design for Asia Awards’ Lifetime Achievement Award 2011. In addition, Ekuan-san has received innumerable awards and held many influential and prestigious design-related positions in his lifetime. He is the founder of GK Design, the internationally important Japanese design consultancy responsible for many notable products, including the Kikkoman soy sauce bottle, Yamaha motorcycles, the Narita NEX express train, the Akita ‘bullet’ train, and virtual environments.

Operating on the principle of “business, movement, research”, his design activities are not just limited to mere design, but expand through design’s social meaning and wider ethos. He has developed the ‘dougu concept’, a Japanese term broadly defining all built things and every man-made product. For Ekuan-san, dougu means a design philosophy for everything that has been created and that views technology and economics as socially viable, with every designed product having a useful existence in its user’s lifetime. He believes the aim of the creative industries should be to create “new value” and having a global vision to solve the many issues impacting society. What can design do to improve pressing global issues? How can problems facing mankind be solved? And how do we all find harmony and peace? His proposition is that we need to contemplate these issues, and create products and systems that nurture our capabilities.

Design is not limited to function and form, but must pioneer creativity to initiate better social and economic value for the future. He insists that the designer must ultimately aim to create a new, truer sense of wellbeing for everyone through design-created values. He has, himself, been a pioneering contributor of industrial design in Japan, playing a key role in the bringing together of designers, business and leading organizations.

His eloquent, ideological writing on the meaning of the design of objects in everyday life and the interpretation of design activities in relation to Japanese cultural life is found in his seminal books, Thoughts on Tools and The Aesthetics of the Japanese Lunchbox.

The Makunouchi Bento, or traditional Japanese lunchbox used in Japanese homes and in restaurants, is a highly lacquered wooden box divided into quadrants (or four equally sized spaces), each containing different food delicacies. As a food container, it initially presents as a simple box, containing food portions residing in its own compartment, and obeying strict lunchbox geometry and food placement etiquette. Ekuan-san metaphorically explains a much deeper interpretation of the lunchbox that unravels Japanese culture, its spirit, form, aesthetics and the ideal that “many can be reduced to one”. He unlocks ancient Japanese design secrets, rituals, celebrations and aesthetics, explores Japanese landscape, and delineates the 48 rules of etiquette of Japanese form. This critique of Japanese design connects everything from food, television, motorcycles, package tours and department stores to the landscape, ecology, computers and radios. Nothing is what it first appears, while everything is explained using his "lunchbox” theory.

Believing in the vision of “the democratisation of design”, Ekuan-san willingly responds to a client’s needs to specially provide product, architecture, packaging and digital technology design solutions. He aims to raise design consciousness by stressing the requirement for sound ethical foundations, utilizing insights into human nature within society’s traditional rules. He firmly supports mastering systematic engineering and manufacturing technology within an economic framework, but insists design’s dreams can only become reality if intelligence and creativity are applied to create a beautiful form which is value added.

Ekuan-san believes that humanizing a machine (e.g. a modern motorcycle), and giving it a formative expression was an epoch-making development in design and society’s history. One of his goals has been to ensure that material things harmoniously and collaboratively coexist in a natural environment with each other, otherwise the reason for its existence will be denied if the coexistence is not materialized. This is achieved by further understanding human nature; otherwise, we will eventually use up all the world’s natural resources. The designed product cannot be valued in and of itself, but we must consider the precious resources required to develop a product. The core mission for designers today is to focus on people’s future lifestyle but within nature’s own constraints and aesthetics.

Ekuan-san’s design philosophy is extended by what he believes is the Japanese concept of attention to others – an attitude differing slightly from a Western approach. He explains in The Aesthetics of the Japanese Lunchbox that Japanese product designers are anxious to accommodate all the universal wishes of users, thus equipping their product with additional functions or devices that, however, most people seldom use. When a product requires extra additional functions, this makes the designer’s job more difficult to create a simple design. Therefore, product design must strive to compensate by being well balanced and simple. Regardless of the designed object, we all need design.

Ekuan-san believes that design’s essential purpose is to serve the people, be they rich or poor. "I look forward,” he said, “ to seeing young designers have the ability to understand that through design they can improve the physical and spiritual lives of 7 billion people on earth, to allow more freedom and democracy. On our earth, only one tenth of the whole population can really enjoy the advantages of the so-called prestige life brought by modern design.”